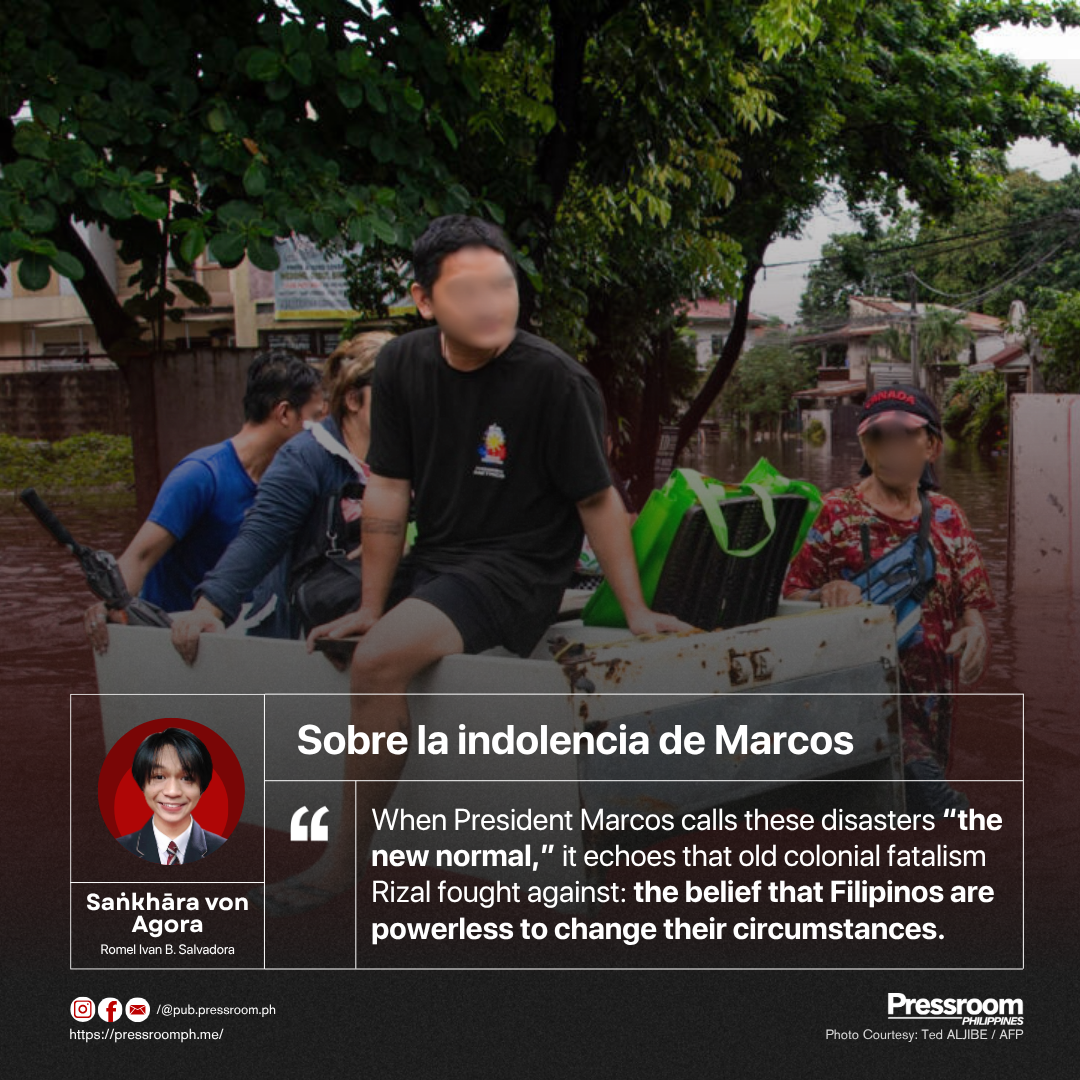

"This is the new normal."

A quote from President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., as floods swallowed entire barangays, landslides reshaped the countryside, and Filipinos once again found themselves waist-deep in murky water. The President’s message was simple: storms are inevitable, disasters are inevitable, and suffering is inevitable. Accept it.

When I read this, I couldn’t help but be reminded of José Rizal’s essay “Sobre la indolencia de los filipinos,” or “The Indolence of the Filipinos.”

I’m no expert on the whole essay, but even a passing glance at that work shows how familiar this tone of resignation is. It’s the same way of dressing up problems as inevitable, the same way people once blamed Filipinos for being lazy under the tropical sun. Now, our own leaders blame the tropical sun for floods they failed to prepare for. Different century, same lazy excuse.

Back in 1890, Rizal penned the essay to dismantle the lazy stereotype slapped onto our ancestors. He didn’t deny the existence of indolence, but he insisted on investigating its roots.

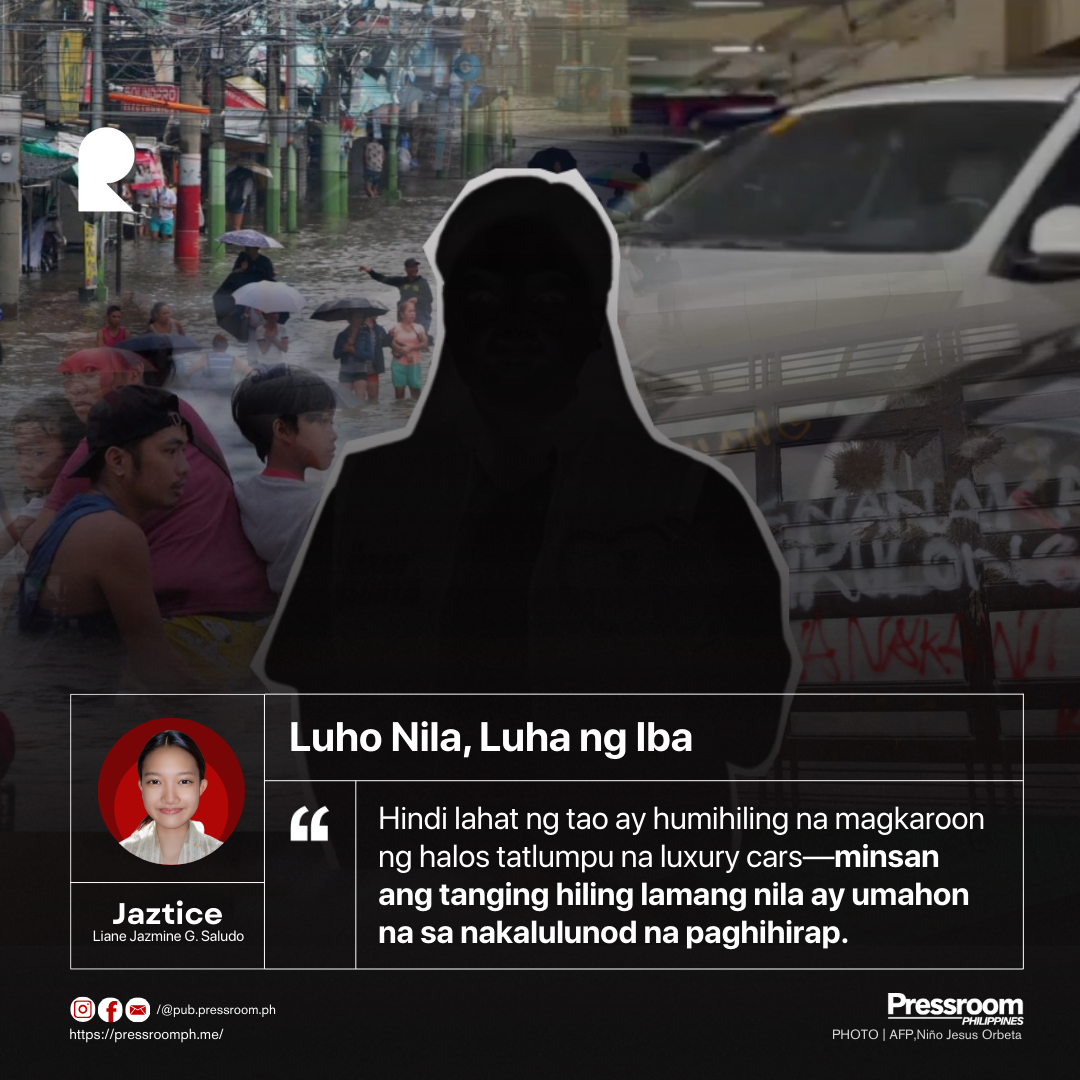

The essay emphasized an idea—a man in a hot climate does not work with the same eagerness and energy as one in a cold climate. Oddly, today that rings a familiar bell. Filipinos are now truly busier than ever, under cold, waist-deep floodwaters, grappling with rescue, salvaging what they can, and fighting to keep their homes afloat. There is no room for indolence when the flood is at your doorstep—and perhaps that’s exactly the problem. You won’t grasp how serious flooding is through the lens of someone watching it from a mansion.

However, while coincidental, that is not the mere point of why indolence in this country exists. Rizal also argued that centuries of oppressive systems bred a society infected with laziness. In other words, indolence, he said, was not natural—it was manufactured by a system that made them settle for complacence.

Fast forward to 2025, and we are witnessing the same system-induced indolence Rizal wrote about; the system that we are supposed to lean on is the first one giving up.

(bold ts paragraph) When President Marcos calls these disasters “the new normal,” it echoes that old colonial fatalism Rizal fought against: the belief that Filipinos are powerless to change their circumstances. Back then, it was used to justify oppression. Today, it’s recycled to excuse complacency.

“New normal” is just a PR-friendly way of saying, “We're not going to do anything differently.” It’s like a doctor telling you, “Your fever is now your default temperature. Learn to live with it.” What they really mean is, “We’re out of medicine, out of budget, and frankly, out of willpower.”

Let’s be clear: Yes, we live in a tropical country. Yes, typhoons are part of our geography. But Rizal warned us against the fatalism of blaming nature for societal stagnation.

He also argued that Filipinos were not always indolent; before colonization, they actively engaged in trade, agriculture, and craftsmanship, thriving within their environment. Laziness, as he explained, was not inborn but developed over years of systemic exploitation and mismanagement.

Today we can see how this intrinsic Filipino industriousness manifests. Just like how you only need to look at places like Agusan, where entire communities build elevated bamboo walkways just to stay mobile during floods.

The will to adapt of the Filipinos was always there. It always has been. Here we learn that to be Filipino is not to be indolent, but to be resilient.

Our environment demands adaptation, not submission. Other nations sitting in typhoon alleys have turned their vulnerability into opportunities for innovation. So why should we settle for calling it the “new normal” when we have always been people who adapt, create, and overcome?

In this lens, the new normal is just an excuse for old habits. It’s the rhetoric of leaders who prefer to manage disasters after they’ve struck, rather than invest in prevention. It’s the narrative of a governance culture that reacts instead of plans, that holds press briefings in flooded gymnasiums rather than builds flood-resilient projects, and of officials that make ayudas a winning prize instead of a willingly given resource for internet clout.

Rizal, in his essay, dissected this very mechanism: “The evil is not that indolence exists more or less latently but that it is fostered and magnified.” In today’s context, the evil isn’t in the storms themselves—it’s in the complacency that precedes them, the indifference that magnifies their impact. Nature may bring the floods, but it’s the system’s neglect that keeps us drowning.

Let’s take a quick tally. How many flood control projects have been delayed? How many climate adaptation funds remain untouched, or worse, misused? How many times have we seen officials wade into floodwaters, pants rolled up, grinning for the cameras, only to disappear once the shutters stop clicking?

Every time we ask, “Baha na naman?” we’re not even asking anymore. We’re just stating a fact. Truly, “Baha na naman.” It’s no longer a question—it’s a resignation. And that, right there, is how indolence is fostered and magnified—not from the people scrambling on rooftops, but from the leadership shrugging while looking down from their comfortable balconies.

But here’s the most dangerous part: when people are told that their suffering is “normal,” they start believing that they deserve no better. This is where the cycle begins—where systemic failures masquerade as inevitabilities, and the people, exhausted and disillusioned, are left to wade through literal and figurative floods.

That is why I would argue that “the new normal” isn’t just an observation—it reflects a policy stance. It’s a polite way of saying, “We’ve accepted defeat, and you should too.” When the people start buying into this defeatist mindset, the cycle completes itself. It aims at a goal: You don’t need to oppress people who have been trained to expect nothing. Fortunately, Filipinos know better.

At this point, it’s tempting to resign ourselves to memes and survival jokes—Filipinos are experts at that. But Rizal didn’t write “The Indolence of the Filipinos” to join the collective sigh. He wrote it to ignite accountability. He knew that to cure a society, one must first diagnose the real disease—not the symptoms, but the systems.

So no, this is not the “new normal.” Instead, it’s the abnormality that comes from the same old excuses. And if Rizal were here today, he’d probably write a late footnote: “Indolence is not inborn; it is imposed.” Which is exactly what’s happening right now.