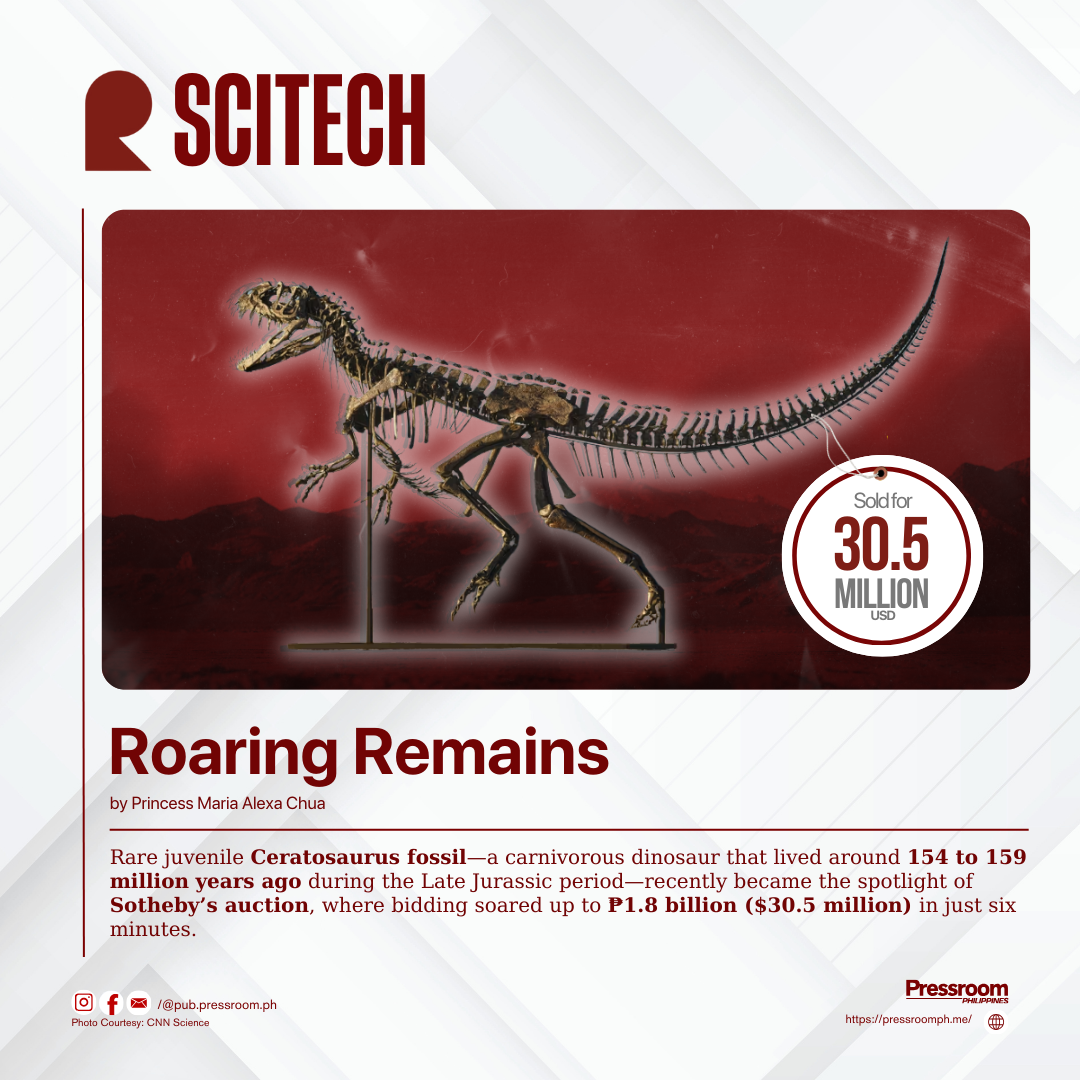

Rare juvenile Ceratosaurus fossil—a carnivorous dinosaur that lived around 154 to 159 million years ago during the Late Jurassic period—recently became the spotlight of Sotheby’s auction, where bidding soared up to ₱1.8 billion ($30.5 million) in just six minutes.

Ceratosaurus is a predator known for its sharp teeth, horned snout, and armor-like skin plates, thriving in what is now known as North America. The fossil’s presence in an auction hall shifts its story from survival and extinction into one of spectacle and commerce. What was once a creature roaming ancient floodplains is now reduced to a price tag—raising questions about memory, ownership, and whether Earth’s history should belong to humanity’s gaze or remain a shared treasure of science.

For millions of years, this juvenile dinosaur lay preserved under rock layers in Wyoming’s Morrison Formation, one of the richest fossil beds in the world. Fossilization itself is an extraordinary process—where bone matter is slowly replaced by minerals, preserving shape and structure over eons. Juvenile fossils are particularly rare because young dinosaurs often had smaller, more fragile bones that were less likely to fossilize.

What makes the discovery unique is that the Ceratosaurus skeleton is about six feet tall, nearly 11 feet long, and contains 139 original bones, including a complete skull. Its smaller frame compared to adults gives paleontologists a chance to study growth stages—how the species hunted, developed muscle structure, and adapted in a competitive ecosystem filled with predators like Allosaurus. Beyond that, the fossil links to other discoveries, such as the Ankylosaurus and Diplodocus found in the same rock layers, collectively piecing together an image of life in the Jurassic landscape.

Turning such a fossil into an auction piece feels like tearing a chapter from Earth’s library and putting it up for sale. While auctions generate excitement, the risk lies in private ownership: many specimens disappear into private vaults, inaccessible to researchers, students, and the public. A fossil is not merely an object—it is a story written in stone. Museums allow people to stand before these remains, imagine the roar that once echoed, and understand evolution as something tangible. When a fossil is hidden away, it ceases to be a teaching tool and becomes only a possession, severing the connection between humanity and its past.

Defenders of fossil auctions argue that private collectors help preserve these treasures. Excavating and restoring fossils demands resources—funding, equipment, and expert labor—that museums sometimes cannot afford. In that sense, wealthy buyers can ensure fossils are not left to erode in the ground. Yet the ethical dilemma is heavy: fossils are not art pieces or jewels; they are biological archives. They carry potential for future studies—such as examining microstructures of bones to estimate growth rates, exploring traces of ancient proteins, or even advancing our knowledge of dinosaur DNA fragments. These insights could change how we understand evolution, survival strategies, and even modern biology. If locked away, that potential is lost—not just to science, but to every future generation that could learn from it.

A Ceratosaurus that once roamed freely without ever knowing humanity now finds its remains bound by human currency and spectacle. What was once part of a world untouched by us is now a commodity shaped by us. This irony forces us to reflect: fossils are not just bones of creatures long gone, but mirrors of our choices in the present. They can either remain vessels of memory, preserved in public institutions, or become possessions behind closed doors. The auction of this fossil is not just about one dinosaur—it’s about how we decide to treat the past. Do we sell it, or do we share it? Because ultimately, the fossil’s greatest value does not lie in millions of pesos or dollars, but in its timeless reminder that life once thrived, roared, and vanished long before humanity even existed.