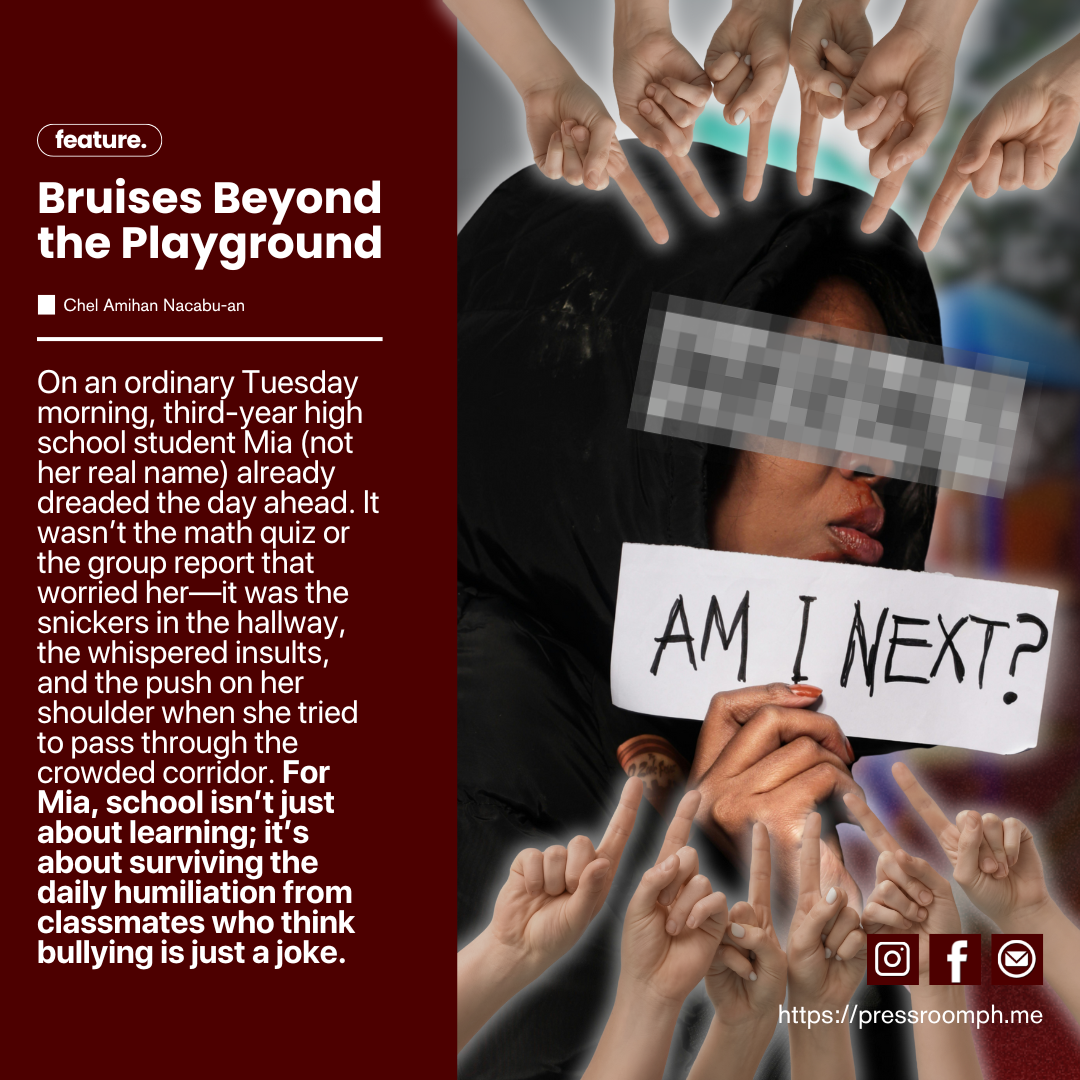

On an ordinary Tuesday morning, third-year high school student Mia (not her real name) already dreaded the day ahead. It wasn’t the math quiz or the group report that worried her—it was the snickers in the hallway, the whispered insults, and the push on her shoulder when she tried to pass through the crowded corridor. For Mia, school isn’t just about learning; it’s about surviving the daily humiliation from classmates who think bullying is just a joke.

Sadly, Mia’s story isn’t isolated. It reflects a reality that many Filipino students face daily.

The numbers that speaks

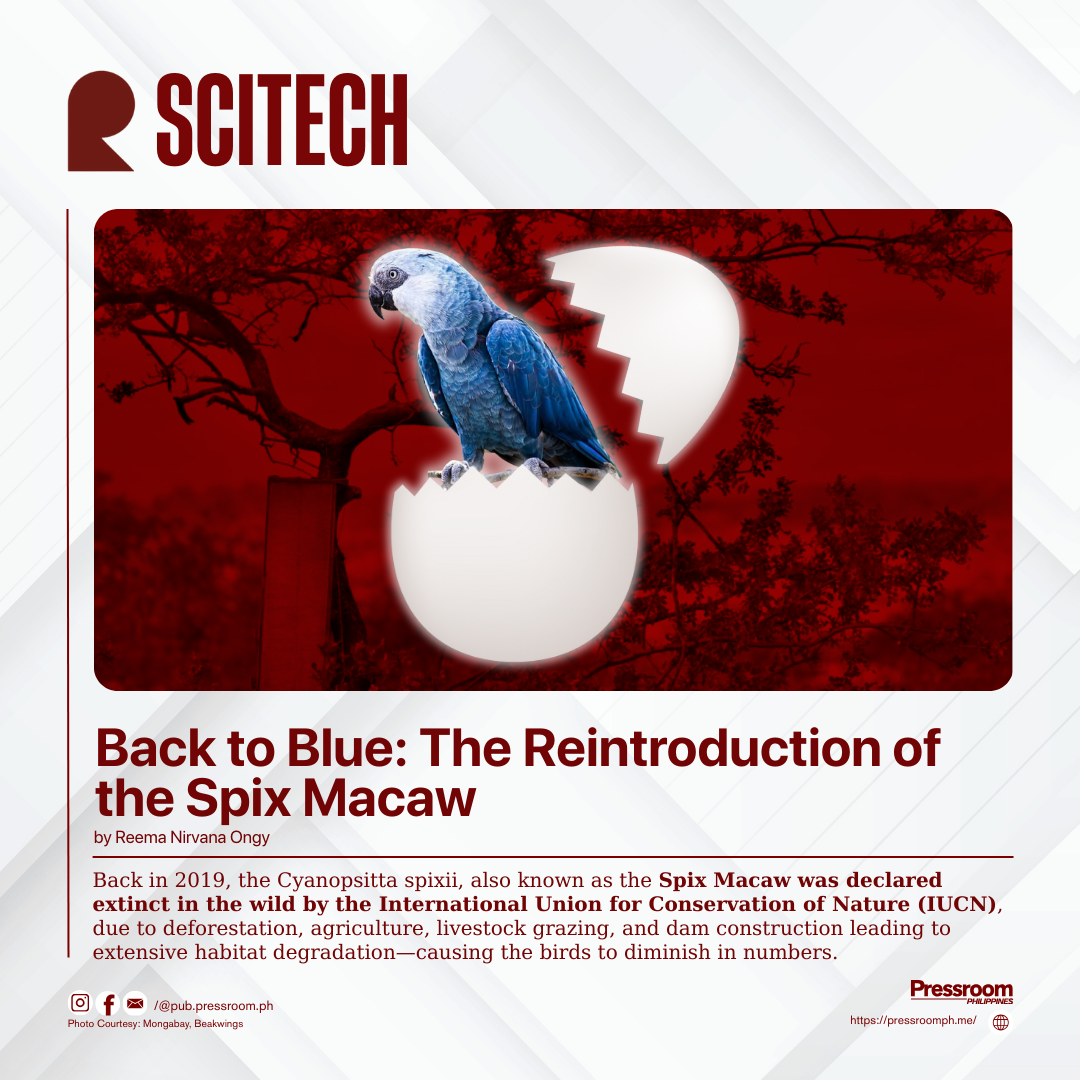

Recent reports from the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM II) paint a troubling picture: almost two out of three Filipino students experience bullying on a regular basis. That’s nearly double the global average, according to international studies.

Dating back, the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) revealed that 65% of Filipino Grade 10 students reported being bullied multiple times each month. While the 2022 PISA results showed slight improvement, the Philippines still remains among the top countries with the highest proportion of students facing harassment weekly—about one in three learners.

These numbers aren’t just statistics on paper. They represent actual children—kids who hesitate to raise their hands in class, who fake being sick to avoid school, and who slowly lose confidence in themselves.

In some classrooms, bullying is almost invisible—masked by laughter or brushed off as “biruan lang.” But for the students on the receiving end, every remark cuts deeper than teachers or classmates might realize. Guidance counselors often describe how bullied students walk into their offices carrying invisible wounds: shaky voices, eyes cast downward, stories they can barely finish telling.

The ripple effects don’t stop with the victims. Classmates who witness bullying often admit they feel helpless, unsure whether to step in or stay silent. Teachers, too, are caught in a delicate position. Some confess that they downplay certain incidents because they lack proper training in conflict resolution or simply because they are already juggling oversized classes.

And then there’s the reality outside school walls. Bullying in the Philippines has taken new forms in the age of social media. A cruel comment posted on Facebook, a humiliating meme shared on group chats, or even exclusion from online groups can leave lasting scars. Unlike in the past, students no longer find refuge at home; their phones carry the insults with them, day and night.

Behind the figures are stories of self-doubt, isolation, and resilience. For every child who suffers in silence, there are also peers who reach out—a seatmate who whispers encouragement, a friend who walks beside them in the hallway.

These small gestures, while not erasing the problem, remind us that even within a system struggling to keep up, acts of kindness still matter.

Silent shortage

If schools are supposed to be safe spaces, why does bullying remain rampant? Part of the answer lies in the country’s shortage of guidance counselors.

International standards recommend one counselor for every 250 students. However, in reality, the Philippines only has around 5,000 licensed counselors for over 47,000 schools nationwide. That means thousands of schools don’t even have one full-time counselor to handle cases like Mia’s. Teachers—already stretched thin with heavy workloads—often act as substitute guidance officers, though most are not fully trained for the job.

The result? Many bullying cases are left unresolved, brushed aside as “normal” school drama, or worse, silenced by the stigma attached to speaking up.

More than just “Kids being kids”

Some parents, meanwhile, shrug it off as part of growing up. “Lahat naman ng bata dumaan diyan,” one father admitted in a PTA meeting, recalling his own school days of being teased. But what he called “harmless pang-aasar” in the ‘90s is no longer the same.

Teachers also notice the toll, even if it doesn’t always appear in the grades right away. For educators already stretched thin, addressing bullying feels like adding another mountain to climb on top of lesson plans, overcrowded classrooms, and administrative tasks.

Yet there are small sparks of resistance. In some schools, student councils are stepping up by organizing campaigns—posters in corridors, spoken word performances, even skits that tackle bullying head-on. These grassroots efforts may not end the problem overnight, but they show young people refusing to normalize cruelty.

What becomes clear is that bullying isn’t just about mean words or childish pranks. It’s about power, culture, and silence. And unless families, teachers, and communities work together to challenge that silence, too many students like Mia will keep walking into classrooms not to learn—but to survive.

Glimpses of hope

Despite the bleak statistics, efforts are underway. Some schools are implementing peer-support groups where students themselves serve as “anti-bullying ambassadors”. The Department of Education has also strengthened the Child Protection Policy, reminding schools of their obligation to safeguard learners.

In several urban schools, student-led campaigns use creative ways—like short films, spoken word poetry, or mural painting—to spread awareness about bullying. These initiatives don’t erase the problem overnight, but they give students a voice, a chance to say: “This isn’t normal, and it shouldn’t be.”

What now?

For Mia and thousands of others like her, the hope is simple: to walk into school without fear, to raise their hands in class without ridicule, and to make friends without the looming threat of humiliation.

Because school should be a place to grow, not a battlefield to survive.

And perhaps the saddest part is how ordinary these stories have become. The jokes, the teasing, the whispers in hallways—things dismissed as everyday school life—leave marks that don’t fade as easily as chalk on a blackboard. Behind the noise of laughter, there are silences that tell a heavier truth: many children carry their battles quietly, hoping one day the world inside their classrooms will finally feel safe.