via Lord Nelson Manuel, Pressroom PH

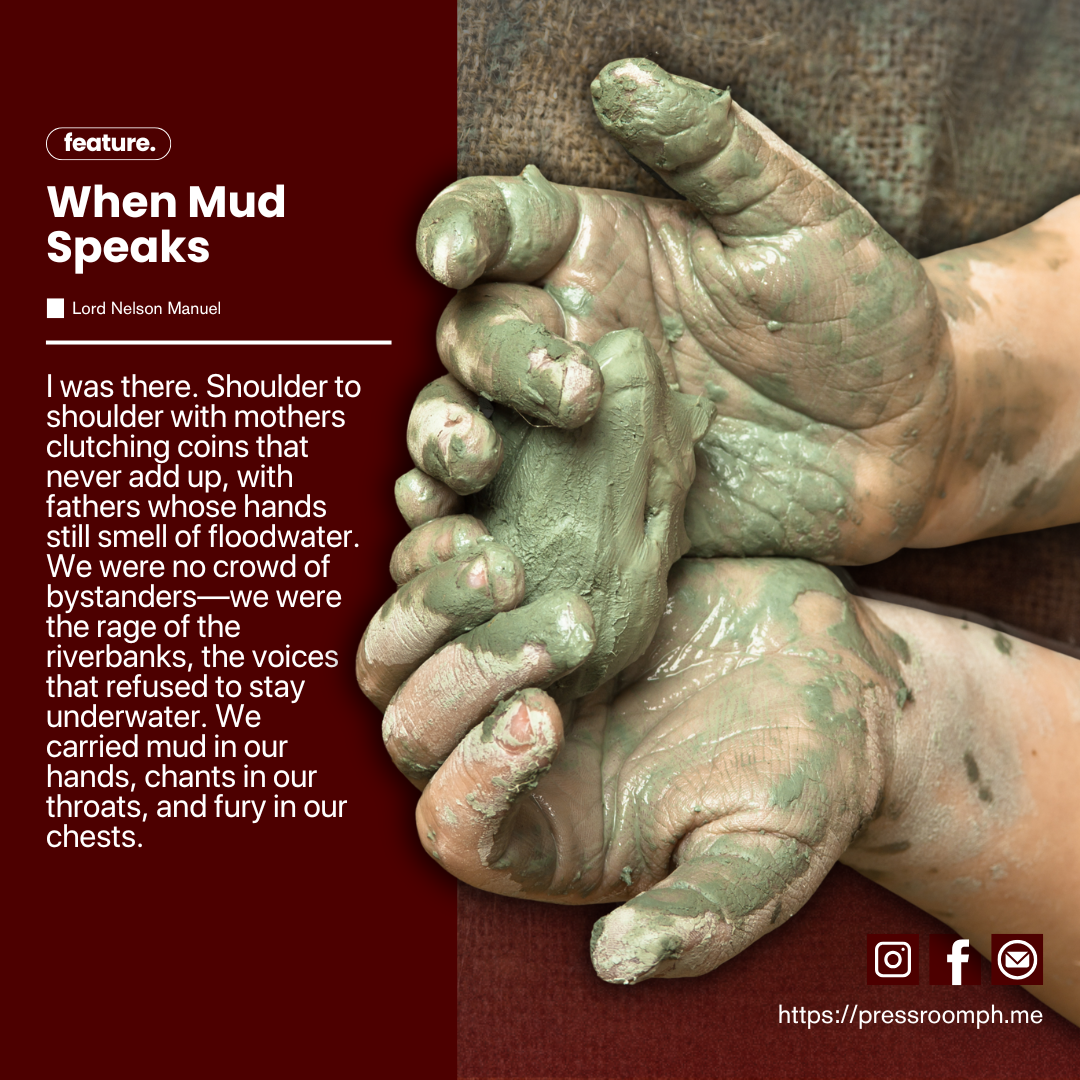

I was there. Shoulder to shoulder with mothers clutching coins that never add up, with fathers whose hands still smell of floodwater. We were no crowd of bystanders—we were the rage of the riverbanks, the voices that refused to stay underwater. We carried mud in our hands, chants in our throats, and fury in our chests.

That morning in Pasig, we walked toward the mansion that stood like a fortress built on stolen steel and ghost projects. The gate was tall, cold, indifferent. We drenched it in mud, smeared it with red paint, scrawled magnanakaw across its iron ribs. It wasn’t vandalism. It was testimony. A reminder that while they dined in silence, we drowned in floods their billions were meant to prevent.

Inside that compound, Sarah and Curlee Discaya did not appear. No glimpse of the woman who once paraded luxury cars while families climbed onto rooftops for safety. No shadow of the man whose companies pocketed contracts while floodwaters swallowed streets. They hid, but we made sure the walls could not.

I pressed my mud-streaked hand against the gate. It felt cold, but it shook. Around me, chants rose: “Katarungan! Panagutin!” Mothers lifted their fists like weapons. Youth waved placards dripping with the same mud that drowned their barangays. That sight was louder than fireworks, heavier than serenity.

Some will say we crossed a line. That protests must be “peaceful.” That due process must take its course. But where was due process when billions were siphoned from flood control projects that controlled nothing? Where was the order when rivers swallowed homes, when bridges existed only on paper, when roads led nowhere but to pockets lined with public money?

What we did was not a disorder. It was a memory. Mud on the gate was not dirt, rather it was the flood itself demanding to be seen.

Look closer at that word we left behind: “magnanakaw”. It was not spray paint on a wall, but a judgment on Discaya’s gates. It shifted the anger of workers who built roads that never reached their own barrios, the grief of families left hungry while public funds fattened private pockets, the fury of youth whose future was stolen to buy tranquility and applause. That word was not an insult—it was evidence. That is why we came, not just to shout, but to stain. To leave a mark that no water hose could wash away.

By sundown, the chants faded, but the gate remained scarred. Under the streetlights, the word burned bright, a wound crying in steel. That scar will haunt the Discayas more than any Senate hearing, because hearings end in papers, but scars unabating.

We did not leave defeated. We left with the truth written in mud. We left knowing we splintered the illusion of untouchable power. We left with the certainty that while they hide behind tinted windows, the people will always find a way to leave their mark.

This fight is not finished. It has only begun.

Because one day, history will not remember the luxury bags, the gowns, the Bentleys and Rolls-Royces tucked inside garages. It will remember the people who came with mud-stained hands and refused to bow. It will remember the day flood survivors stood before a mansion and turned their grief into a verdict. If a gate covered in mud can’t be ignored, then neither can the billion-peso questions left behind by the Discaya’s. And if we keep asking with our words, our bodies, our muddy proof, then maybe history will remember who stood with the drowned and who dined while we were being buried alive.

And that deliverance was clear: The mud on Discaya’s gate is the people’s judgment. And it will not wash away. We came for answers. We left with mud-stained truth. And it will not wash away.