September 21 has never been just another day on the calendar to us Filipinos. It is the drumbeat we cannot escape—the day when Ferdinand Marcos Sr. shackled a nation under Martial Law in 1972, the day Rodrigo Duterte decades later repackaged as a “National Day of Protest,” and now, in 2025, the day when Filipinos once more find themselves marching in the streets against the same heirs of corruption that we already once dethroned before.

Like a funeral procession that refuses to end, every September 21 is our endless reminder that the wounds of history still bleed, and to stop making steps means to stop mourning the future we could have built, had we only, really, acknowledged the past.

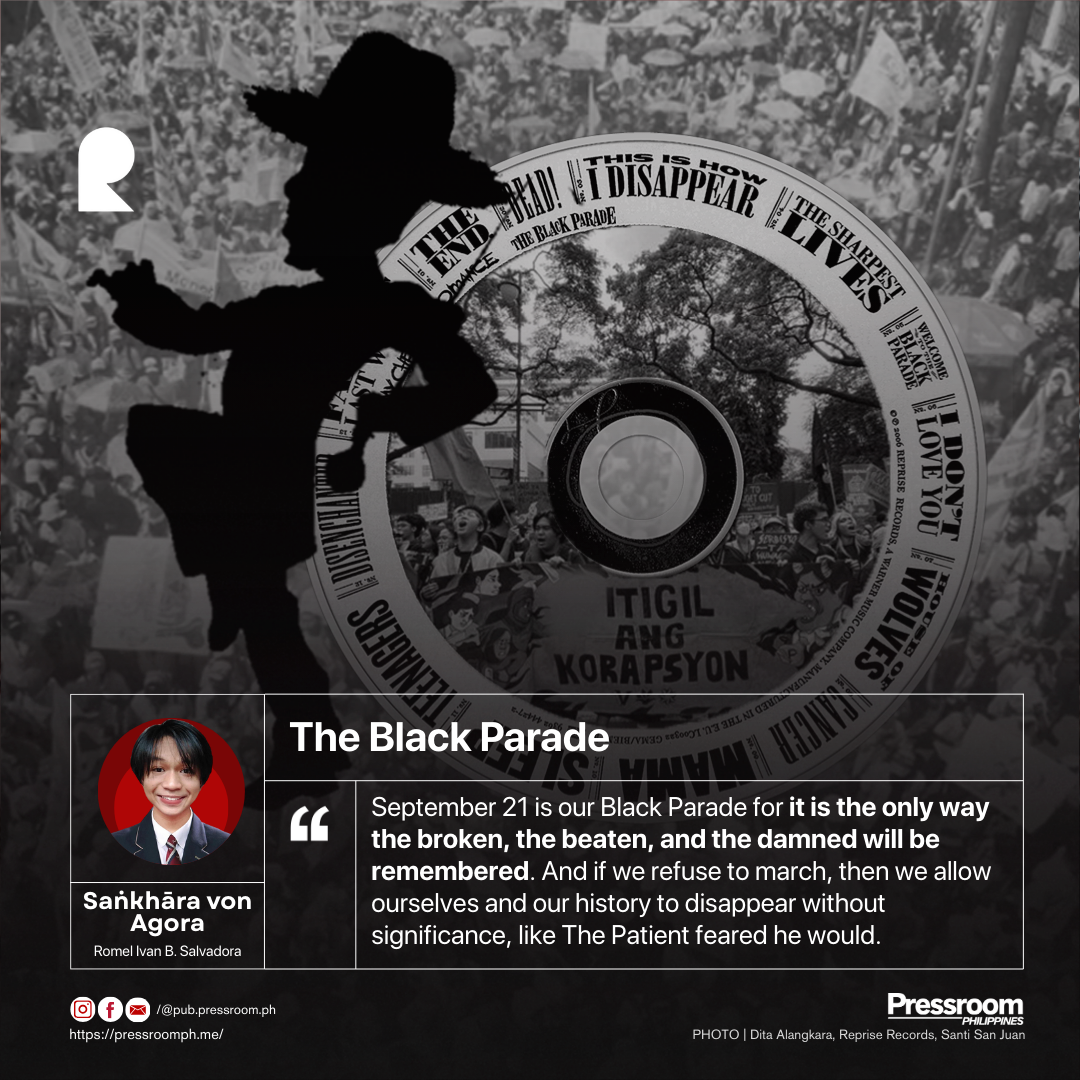

This year’s mobilizations are largely called the “Baha sa Luneta: Aksyon na Laban sa Korapsyon” at Rizal Park, and the “Trillion Peso March” at the EDSA People Power Monument. But with groups urging protestors to wear black shirts and masks during the fated day, I’d call it our own Black Parade.

To understand this, one must understand The Black Parade, an album by the American rock band My Chemical Romance. The album tells the story of “The Patient,” a man dying of cancer who, in his final moments, reflects on his life, his regrets, his loved ones, and the legacy he leaves behind. Death comes for him not as silence, but as a parade—a last spectacle that forces him to confront what it means to live, and what it means to be remembered.

Is this not, in many ways, our story as a nation?

“Now come one, come all to this tragic affair.”

Every September 21, (or daily, even) we are The Patient on his deathbed. Martial Law reminds us of how fragile freedom is, how quickly it can be stolen.

Marcos Sr. signed Proclamation 1081 in 1972, and the Philippines was plunged into its darkest era. Thousands were jailed, tortured, and some, only ever declared disappeared.

Like The Patient succumbing to his cancer, we were told not to expect tears, only submission. Yet, the people still cried out, even through the temptation of only succumbing to fear.

In “Dead!”, The Patient realizes too late that he has wasted his life, that his time is up. Is this not us when we look back at decades of corruption, from dictatorship to dynasties to electing the same old corrupt politicians to ignore flood control projects? How many times must we hear that our nation has “two weeks to live” with all these scandals before we stop laughing at the absurdity and start questioning the injustice?

“And when you're gone, we want you all to know. We'll carry on.”

In “Welcome to the Black Parade,” The Patient recalls his father taking him to a parade as a child, telling him to be the savior of the broken, the beaten, and the damned. While the black parade can be interpreted as the form of death itself, there was also an underlying yet undeniable hope. A hope of carrying on for those who cannot march anymore.

Every protest on September 21 is, in this sense, a parade for the dead. For Martial Law victims, for drug war casualties, for journalists silenced. We march not only for ourselves, but for those robbed of the chance to march.

“I am not afraid to keep on living, I am not afraid to walk this world alone.”

The album ends with defiance. In “Famous Last Words,” The Patient, though battered, though dying, refuses to be silenced. He declares he will live on despite the odds. This is also where we, as a people, must land.

We march not only because of desperation, but because of hope. A hope that corruption can be fought, that Martial Law’s lessons can be remembered, that our leaders’ betrayals can be answered with the people’s solidarity.

September 21 is our Black Parade for it is the only way the broken, the beaten, and the damned will be remembered. And if we refuse to march, then we allow ourselves and our history to disappear without significance, like The Patient feared he would.

Like in the song “Disenchanted”, too many Filipinos risk looking back one day and realizing they wasted their lives waiting—waiting for leaders to change, for the system to fix itself, for justice to arrive without struggle.

The song’s bitter regret, the sense of a “lifelong wait for a hospital stay,” is a warning against complacency. If we treat politics, protests, and activism as a hopeless joke, something to sneer at but never to confront, then we surrender our power and waste the chance to shape a future worth living in. The tragedy isn’t only in dying unfulfilled—it’s in living passively, when we could have fought for something better.

So let the streets be filled. Let us wear our black masks not to hide, but to embody the memory of those silenced. Let us march in our own Black Parade—not of death, but of resistance.

Because history only forgets if we let it.

Thus, September 21 is our own Black Parade. We, too, are the Patient: a nation long-sickened by corruption, betrayed by leaders who treated public funds and seats of power as their inheritance. The “illness” of the Patient — cancer consuming his body — mirrors the cancer of systemic and repetitive theft and abuse consuming our society. And just as the Patient faces death with both mourning and defiance, Filipinos face September 21 with grief for our past but also fury for our present.

And just as MCR’s imagery is gothic, if not apocalyptic, so too is our reality. Corruption is not simply theft; it is decay. It is the slow rot of democracy. It is the tumor that grows each time politicians escape the people’s judgment and justice.

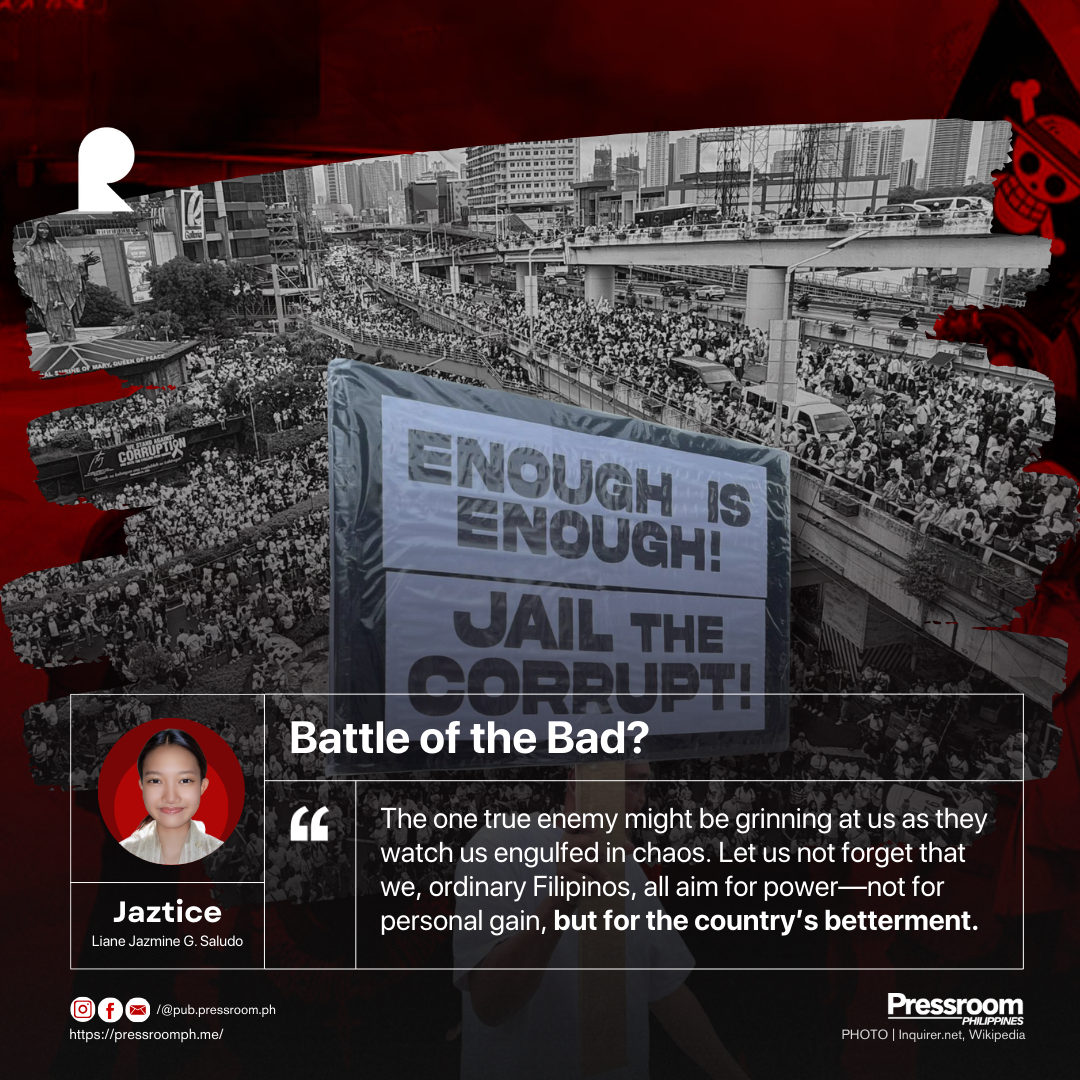

However, a certain group of people that will also plan to march though? Unfortunately, I wouldn’t even consider them walking for justice at all, but for the denial of it.

These particular marchers will carry banners not for the fallen, but for Rodrigo Duterte—the man who turned the nation into his own funeral. To them, they will have a march for order. In truth, it is a parade not of remembrance, but of forgetting. A parade only for their fallen one, forgetting that he’s the reason why more graves existed since then in the first place.

I guess they took the lyrics “And when we go, don't blame us. We'll let the fires just bathe us” too literally.

When they cry for Duterte’s homecoming, it feels more like begging for more cancer than cure. They hold on to the illusion that he saved the nation, when in fact his legacy is a sickness we still struggle to cut out. To cling to him is to settle for further decay.

Now, expecting that there will be two competing parades that will commence, we must ask ourselves: which parade are we willing to walk in? The one that commemorates the dead so they are never forgotten, or the one that pretends they never existed?

May this upcoming event serve as a metaphor that teaches us how to see protest differently. A protest is not chaos; it is the reaction to the chaos. It is also grief set to rhythm, rage choreographed into motion. It is theater that makes the invisible visible.

And if you listen carefully on that day, you will hear it: not guitars, not drums, but the pounding of thousands of feet on the pavement, chanting in unison. That is our anthem. That is our dirge. That is our defiance.

To those in power: do not mistake this for mourning alone. MCR’s Patient did not quietly just accept death, and neither will we. Our Black Parade is not just for the dead we honor, but for the living we refuse to abandon. This parade also serves as a way to say that yes, we may have a funeral, but we refuse to give up and just bury ourselves without expressing our mourning through protest.

The Philippines, almost 40 years since, is still the sick man of Asia—and corruption is still our cancer.

September 21 is the day we march—not into death, but into resistance. Welcome to the Black Parade.